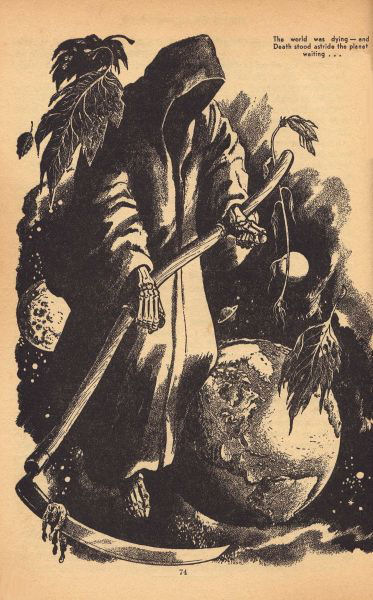

Chlorophyl is that green stuff in plants and it means life to the earth and to all the animals that live on its flowering surface.

BEADS of sweat stood out on Bart Gifford's forehead. He placed the hypo on the table. His arms, bare to the elbow, were streaked with green. Gifford's shoulders were broad and his tall body seemed to indicate great strength, yet as he leaned over the tiny test-tube of green jelly, his fingers shook.

He straightened, looking worried. He waited for five minutes, hardly moving, his eyes on the test tube . . .

Outside, hoofbeats disturbed the quiet summer afternoon. They slowed to a steady clip-clop near the corral. Gifford sighed and took off his shirt.

He washed in a small lavatory in one corner of the room, found a fresh shirt in the closet and put it on. As he went to the door, he stopped to take a last look at the test tube. The stuff in it was still green.

He frowned and went outside. A hall led him to a wide, screened porch. Beyond the porch was a wide, dusty yard, the corral and the prairie. Far beyond the prairie, the Teton Mountains arose in jagged, tooth-like formation toward the hot sky.

Jeff Stern was coming up from the corral. His face was dusty and his eyes looked dull and almost frightened. His face was made up of sharp angles cut by a stern, straight mouth. He slumped down into a chair beside Gifford.

"Hello, Jeff," Gifford said. "How did it. go today?"

Jeff Stern turned slowly. His voice was full of despair.

"You know damn well how it went. Bart, I got to know what it's all about."

Gifford tried to smile. It wasn't any good. No, he couldn't tell Stern that the world was dying. People couldn't be told that. They had to go on trusting, believing.

"Nothing wrong, Jeff," he said. Atmospheris condition. We've had a long, dry summer. When the rains come, everything will be okay again."

Stern stared down at the dusty earth, the dried-up flower beds.

After a while he said:

"You came here for a purpose, Bart. The Institute doesn't waste its best men on wild goose chases. You brought lab material with you. You've been in ten different states, and you've been getting code wires from China, England and all over the map."

His black, snapping eyes appealed to Gifford for help.

"The wild things are dying, Bart. Are they gonna keep on dying?"

Gifford was thinking.

I wish to God I knew, he thought. I wish I could see into the future. He shrugged.

"I -- I can't talk now, Jeff," Gifford said. "You see, it's a big problem. Maybe a hundred men of science know, or think they know what's going on. If they let the information out to the layman, well, there'd be a panic. People don't react gracefully to such things. They are apt to go back to animal standards. To murder and fight, and make things generally worse for themselves."

STERN said nothing -- waited. He was sure that Bart Gifford wanted to say more.

"I'm a man, Bart," Stern said. "I was shooting my way into this country before you were born. I can keep my mouth shut. I been thinking that things weren't going to be good. The grass is dead on the north range. The cottonwoods are hanging limp, like bodies with the blood gone out of them. I want to know why."

Bart Gifford sighed.

"You have to know sometime," he said in a low voice. "Everyone has to know. The plants are dying, Jeff. Every form of plant life, dying for no reason that we can fathom. Do you know what that means?"

He leaned forward, gripping the arms of his chair. The panic that had been in his brain for weeks now -- months -- showed in dark smouldering eyes.

"Do you know what that means?"

The same question, asked a million times a day, and never answered. The same frightened, bewildered voices. The voices of men who wanted to know. Had to know if they were to find a way to save the human race.

"Do you know what that means?"

Professor Hiram H. Biggs, Naturalist, Bangor, Maine, in an interview with reporters of the New York Times, one month later:

"Gentlemen, I'm only a man. I've lived in the woods all my life. You can tell your people for me that I have no explanation. I noticed during the early summer months that the smaller plants were dying. I could find no reason for this. Study under the microscope shows that plant cells are drying up -- becoming unfit to reproduce. The forests north of Moosehead Lake are dead. Pine trees, brown, rattling their dead limbs in the wind -- that lost world is creeping south. Maine is giving up to death. The life blood of the state, and of the world, chlorophyl, is dying."

They didn't know much about chlorophyl, these reporters who visited the first state to die. They went to Harvard and talked with Bertram, world renowned chemist and biologist.

"Gentlemen," Bertram told them, and his eyes were sad, "Chlorophyl is the basis of all life. It is the life blood of every plant and thus, our life blood. Chlorophyl, if you will have an explanation, is the perfect alchemist. It transmits sunlight into living tissue. That tissue gives us our food, our necessary raw materials, even the precious air we breathe."

Bertram sighed.

"Chlorophyl is refusing to, do its work. It is dying. That means that the human race must die with it."

When he finished, the fifteen men who had come to listen, asked many questions. Each was answered, each -- that is, but the last.

"What are we going to do about it? Men have faced big problems before. They can surely solve this one?"

Silence, then a thoughtful, slowly spoken answer.

"Men are small. No larger than the ant tribe, if you compare them with the plant world. The plant world came first. It outlived everything else. It supported life and nourished it. If the plants die, we die. There is no answer to that."

And so, news went out to the world explaining why the summer was so uncomfortable, dry and hot. Nothing serious yet, the papers said. Just sections of the country touched by the mysterious finger of death. Dry, burned forests and dusty, plantless fields. The finger of death, pointing lightly at man. Pointing, and leaving it a mark.

The United Vegetable Producers of Southern California -- Report to the Nation published in all national magazines, August 1954 --

"We regret that we will no longer be able to supply the nation with our speedy, refrigerated service. Crops this year dropped to a point where shipping is impossible. All fruits were blighted. Vegetables turned brown and plants died, even in our lush valleys of California. The government offers us no solution for the strange disease that has stricken our lands. A group of our experts is at work . . ."

The report filled three pages.

No more vegetables for the tables of New York, Chicago and the thousands of towns served by this company and others like it.

SEPTEMBER 1954 -- The United States today is living chiefly on meats, but the quality of meat is growing poor. No feed is obtainable and pasturage is slim. Vegetables are quite out of the question, save for the runty variety of plants nourished in our small Life Blood gardens. Health standards are down and doctors advise mothers to consider the question carefully before bearing children. The situation is bad. We are the first to admit this. Some hope is felt that the group of one hundred men of science, working with this administration, will affect a solution . . ."

Partial Report of the Department of Agriculture.

Some hope is felt.

Shanghai, China, October 16, 1954 -- Fifteen thousand peasants died this week in Shanghai. There is no food, and there will be none. China, oldest of countries, has faced famine and war. It has survived untold centuries. Now, because nature has so chosen, it dies. It strangles and starves and chokes, a huge nation, lost because plants refuse to grow.

London, England, same date -- The London Times today stated that country people should make every attempt to keep their gardens watered, free of insects and carefully weeded. Although the situation facing the Kingdom is no doubt serious, Parliament will meet next week to . . ."

Parliament will meet next week.

Parliament could meet next week, and every day following that. There was one thing the people could not grasp. This was not a war. It wasn't anything you could handle by laws.

The plants were dying, and when they died, the world died. It would become a dry, hot dust ball, on which no man could live. The oxygen, thrown off by the plants, would not be here to breathe. The animals could not feed on plants and the men could not remain to live on animals, and there it was -- like that childish poem -- something about the pig bit the cow and the cow bit -- senseless, like this was senseless. No plants, no food, no air. Death.

Some hope is felt.

Man is warmed by the sun. Without the sun, man cannot live. You learned it in school -- lower grade.

But -- man still had his precious sun, and he could do nothing with it. It burned each day, a fiery, dully furious ball, sucking up moisture and giving nothing in return.

"Why?

Because, for untold centuries, men had failed in a simple task. Failed to convert the sun's rays into living tissue.

Chlorophyl did that. It performed the delicate, seemingly impossible chemical change in less than a second. It fed the insects, the birds, and the animals. It breathed up the poisons of the earth and sent off pure air.

Could man do it without the plants? Man had tried for centuries to duplicate the job of chlorophyl. The answer was no.

Some hope is felt.

BART GIFFORD, neat, well dressed, always hopeful, stood at the head of the long table. There were many men here. Some greater than he, some from more humble places. They made up the last pool -- the last group on earth who might save the race. They weren't hopeful.

Gifford said:

"We know what the situation is now. We know that this wasn't caused by anything man can remedy. When the flood comes, no dam will stop it. When the rains come, we don't shut them off. This is no blight. It isn't . caused by insects. We have decided that there is no explanation. The plant world is tired. Many times before, parts of it have died and others have arisen to take over. This time, the whole world of plants is dying. We can't prevent it. Every country of the world has reported like conditions. Slowly, as though death were pleasant, forests dry up and become lifeless. There is no material that we can mention that will not be cut off from us. The air itself will become deadly."

He hit the table lightly with his open palm.

"Therefore, I say we cannot longer deceive the people. When the worst is known, they will prepare themselves and know what to expect. There will be panic. Some will be at ease for the first time in months, when all their doubts are cast aside.

"I say that we should release our findings to the world and let it prepare itself for death."

A sigh hissed through the chamber. A sigh so gentle that it might have passed for one man, breathing his last, cool breath of air. Then a vote was taken. The world must know the truth.

Men sat late that night, pooling their knowledge, preparing the report to the world. A world doomed because green things would no longer be green, and air and food would be choked off, leaving nothing but poison and death.

How it was in other countries, one does not know. The United States is huge, and the misery there was a reflection, slightly better or worse, of what went on throughout the world.

The pace of a man's walk was changed. He walked slowly, dragging his feet. Factories closed, for no one would buy their products. Food was still here, but in small quantities, for the gardens did not die all at once. They died slowly, and everything fit for storage was treasured at high, black market prices. Murders were many and few crimes were solved. Man's hatred and desire for revenge grew great. Short tempers -- poor nerves -- shrinking bodies.

Maine was deserted. California was a desert, dry and dusty in the Spring of 1955.

The South no longer had deep green swamps. They were mud holes, with gaunt, leafless trees hanging over them. Beneath the water, huge alligators tore each other apart and fish fed on fish, the weak dying first. The strong held on.

All animals have much in common.

The weak die first.

BART GIFFORD'S coupe sped down the last stretch of concrete road toward Lansing. He had enjoyed coming here in years past. There was a small lake on Lem Water's farm, just north of Lansing. A lake where the Waters and the Sterns of Wyoming met every year to live peacefully for a month, bathing, fishing and relaxing.

Lem Waters always cleaned the big cabin in the pines just before the Stern family arrived. He swept it out carefully, and laid logs in the rock fireplace for that first night when old friends meet. "Peachy" Waters, childhood pal of Gifford's, the yellow-haired kid who had ducked him for the first time in the blue water of the little lake, made the beds and put a couple of pine cones under Giffords' pillow. She was a sweet kid, he thought soberly. Too bad her kind had to die.

He started feeling a little happier after he left Lansing and turned North. It wasn't really happiness he felt. It was the automatic recurrence of an emotion he had felt for years at this time, and it made him feel warm and excited, at least for a time.

Gifford had grown up with the Waters family. Grown up and gone through Harvard to return each summer for this one month of complete relaxation.

Lem Waters and Jeff Stern had been boyhood pals until Stern went West. That made the party just right, Gifford thought.

Lem and Jenny Waters, and Jeff and Dora Stern. Then, Peachy with her girlish, laughing fun, and -- Jane.

He pushed Jane Stern out of his mind abruptly. None of that this summer, he told himself. Love and death don't mix.

"Till death do us part."

No room for sentiment, at least until the problem was solved or the race was dead.

He reached the hill above Gifford Point, where you could look down into the pine filled valley and see the round, depthless blue of the lake. It took his breath away, and he remembered Peabody's last letter.

"The lake is the same. The trees are still green. We're quite happy. We'll be looking for you."

He fed the coupe a little more gas, turned on two wheels down the muddy, rutted road that led across Lem's pasture. The cabin was in sight, nestled among the evergeens. The cabin was brown and rich looking with grey-blue smoke drifting up from the stone chimney. It looked secure, locked away from the rest of the world.

He saw Jeff Stern's Cadillac parked near the door. He took a quick breath. In spite of his resolutions not to let Jane affect him this year, his heart started beating a little faster.

He drove up beside the Cadillac and parked. He started to get out. A girl, small, beautifully slim, came out of the house. Her blonde hair waved gently in the breeze and the sun glinted on her frock, the color of her hair.

"Bart -- you did come."

She ran toward him, her arms open, and he was prepared for her.

"Peachy?"

There was a question in his voice. A puzzled, bewildered question. Peachy always came to him like this. Brother and sister. Pals. He would grasp her by the elbows and lift her, kicking and screaming, into the air.

This time she melted against him, her head on his shoulder.

"Peachy," he said, and his throat was all choked. "Lord, how you've grown, Sis."

The warmth of her was exciting, and it made him angry at himself.

JEFF STERN came out on the screened porch, and the others followed. They were shaking hands, and Bart was kissing the older ladies on their foreheads. Peachy stood close by staring at him with deep blue eyes, waiting for them to be alone again.

He knew that. He knew it so surely that it made him nervous.

Jane Stern came out last. Her blue-black hair made a startling contrast to Peachy Water's golden fluff.

Jane was Gifford's age, slim, sophisticated, finishing school material. She took his hand and it was warm and dry. She stared into his eyes, telling him she remembered all his words, every kiss. Telling him she wanted him.

"It's nice of you, Bart, to come when -- things are so . . ."

Her voice broke, and a shudder shook her body.

"Hey," Jeff Stern said in a loud voice, "Bart's hungry. We're all hungry. Bet those pancakes are burning right now."

Jenny Waters, tiny, honest-faced, and full of the responsibility that was hers, uttered a flustered:

"Oh!"

She rushed back into the cabin, and her husband, Lem, started to chuckle.

"Leave it to Jenny," he said. "The pancakes will survive until we get to them."

They all went inside, and Gifford washed and put on a clean shirt. When he came down from his room, his mind was on the pine cones Peachy had left on his pillow. They made the room smell wild and clean. They made him wonder about Peachy, and how she had grown.

She wasn't in the kitchen. The others sat down with him at the big pine table and they ate. No one mentioned Peachy. Once, staring out the window toward the lake, he thought he saw her bright dress fluttering against the blue of the water.

Peachy was down on the dock, alone.

He looked from one face to another, seeking an answer. No one gave away Peachy's secret. No one, perhaps, but Jane. He didn't question it then, but Jane's smile was possessive, and perhaps a little too sure. He wondered how Jane would stand up when the world really started to go to pieces. He decided that her nerves were strong. She wouldn't break.

The three men sat alone in the flickering light of the fireplace. Their faces were sober. The women were in bed. It was the first night. The first night at the tiny lake where life had fought to remain life -- and was still green and good.

Lem Waters had a stern face. A thin face, with kindly eyes. His eyes, Gifford decided, were really a reflection from his heart. They were brown and depthless. They gave off a light of goodness.

"To me," he was saying quietly, "it don't mean so much. Perhaps I'm selfish, but I'm tired too. I've worked hard for sixty years. Mom, she's ready. They can't tear us apart, Hell or Heaven."

He sighed and his head bent forward heavily.

"It's Peachy I'm worried about. She's young, and there's a million more young ones like her. They've just tasted life. They ain't ready for to meet the Almighty. It's tough on Peachy."

Was that why Peachy stayed away from dinner, Gifford wondered? Was she frightened, trying to run away from death?

"Take me, now," Jeff Stern, "damned if I want to die. I'm a fighter, Lem. I fought my way west fifty years ago. Dug and scraped and built me a home where there wasn't nothing but sagebrush and cactus. Dora's a strong woman, and so's Jane. Jane's gonna take it all right. We've talked it over. Jane's younger. She'll live the longest."

GIFFORD closed his fists tightly. It was hard, listening like this. Listening to a billion people all over the world, waiting to die, preparing for it in different ways. Some of them took their own lives, because they couldn't stand the strain.

"She'll take care of Mom and me,"Stern was saying. "We got a grove of cottonwoods down by the creek. Nice place to be."

He grinned apologetically.

"Of course, them cottonwoods don't look like they used to. Mom and me planted 'em forty years ago. They started with us, and darned if we didn't outlive 'em."

"By a little while, anyhow," he added softly.

"What you think about it, Bart?" Lem Waters asked.

"Huh?" Bart Gifford was thinking of the cottonwoods, dry and lifeless.

The Sequoia would be the last trees to die, he thought. The mighty trees that grew on the west coast. The trees that had survived everything. Born before Christ, the great trees had heard pterodactyls battering their huge bat-like wings among their branches. Trees that had witnessed the evolution of the mammals and watched prehistoric rodents gnaw at the shells of dinosaur eggs.

"I said, when do you think it will come The final reckoning, that is? How long you think we got?"

Gifford shook his head.

Don't tell them. Don't tell them.

When will it come, they ask? It will come in a month, weeks maybe. No more vegetables from the great producing states. A few more head of cattle from places like his. A few wild animals, snared and shot by starving people. Then no food, even for the animals, and you go out and shoot at starved, diseased things unfit for food. The air is bad to breathe. It will be worse. A vacuum of poison will sweep in, and finally, nothing.

"I don't know," he tried to sound cheerful about it. "Of course, there's still hope."

"There's still hope."

Jane Stern heard him say it at breakfast, and her eyes went from face to face, searching first one and then the other. Her heart beat wildly. Could she believe? Jane Stern was frightened. Frightened mostly of herself.

Randy Williams came down from Tawas that morning. Randy, old friend of Jane, had received a letter from her only last week.

"Dear Randy

Remember the fun we had in school? I'm coming East again this summer. Will you come and see me? Dad says you are welcome to stay at the cabin on Mr. Water's farm. It's a nice place, really. A little dead, but pleasant. Things are pretty bad here . . ."

Things are pretty bad here. There was more to the letter, but that was the one line that betrayed Jane's fear. She needed friends. Needed Randy, and Bart Gifford, and her Dad, strong and ready to fight.

Randy Williams was handsome. He handled the road work for a big contracting firm at Tawas. He was twenty-six and had a keen jaw, dark eyes and a way of smiling at women that made them excited by his presence.

By noon he was established in the last bedroom and they were all sitting along the dock watching Brad Gifford and Jane racing back and forth from the raft to the beach.

Randy Williams took possession of Peachy.

"Jane said you were nice," he said, making sure that the others were too far away to hear, "but I didn't expect an angel to be waiting for me here."

Peachy was watching Brad. Watching his brown, well muscled arms as they flailed at the water. Watching Jane, slim confident, keeping up with him.

"Thanks," she said. "I suppose I owe you a quarter for that compliment?"

Williams was at ease, confident. "Not a penny," he said. "Shall we swim?"

She accepted the challenge and they stepped into the clear water and headed for the raft.

A new friendship was born. Born when death was close.

They all felt it -- feared it. They tried to ignore it and each played a part in the drama.

It was at night, when darkness hung over the lake and night birds whistled plaintively, that the hurt came. Then, each lay in his or her bed panting, trying to get enough of the sweet, warm air. Each fought terror by prayer or by cursing at what was to come.

Brad Gifford didn't fight. He waited -- still hoping -- always confident that if death came, he could face it.

Then the blight hit Lem Waters' tiny valley. It came in the night, and in the morning, its deadly, colorless hand was above them, the finger of death bringing something inexplainable that sucked up the green of living things and left them burned and fallen.

Death to one man is bad.

Death to a world is almost more than a mind can stand. It does something to man's soul, searing it over -- killing his faith. When all hope is gone, it kills the body where the soul was housed.

BRAD GIFFORD found it first. Found the tiny evergreen, hardly over a foot high, with its sapless little trunk and brown needles. Because he was a lover of nature, he brought the sapling into the cabin as tenderly as he would carry a child. He placed it on the table. They were all there. Jane and her mother were talking in the corner, looking out of the window at the lake. Peachy and Randy Williams were conversing seriously near the fireplace. Stern and Waters were in the kitchen, taking their turn at washing the breakfast dishes.

"It's come," Gifford said. Something in his voice startled them. Something final, as though he was reading a death warrant. The conversation stopped. Dora Stern came to the table and stared down at the sapling.

"Burned," she said, almost in a whisper. "Just like the evergreens on the north range.

"Burned?"

"No, just sucked dry. Dead, without green -- without life -- "

Without chlorophyl.

Randy Williams came over, picked up the evergreen, then tossed it on the table again. His lips curled slightly as he regarded Gifford.

"Trying to scare us?"

His voice was challenging.

Gifford said nothing. He knew little of Williams. Williams had come at Jane's invitation. Now Williams was paying too much attention to Peachy. Why that troubled him, Gifford couldn't guess. There was something about the man he didn't like. Didn't want Peachy near him.

"There is no reason for anyone to frighten anyone else." The voice was Jeff Stern's. He stood in the door, an apron tied around his waist. "Bart brought the tree in because he's been watching for some sign of the blight here. It's missed us so far. It's coming, and there's no use taking the thing lightly. There's one thing we can't escape and we want to know when it will come."

He didn't say death. They all knew it. Still, he couldn't use the word.

Randy Williams grinned a little crookedly.

"Science will see us through," he said. "Why, I was in Canada last week. There are miles and miles of good timber left. This blight will leave before it effects the whole world. Everything's going to come out all right."

He wheeled and faced Peachy Waters.

"Game for a swim?" he asked. "Things are too darned serious in here."

Peachy looked first at Bart, then at her father. She wasn't smiling. Then she shrugged her shoulders.

"Game for anything," she said. Her voice sounded weary.

They went out together.

The rest of the group gathered around the table. Jane came close to Bart Gifford and linked her arm in his.

"How long now?"

Her hold tightened. Her fingers pinched his flesh. He should have been flattered, pleased. Somehow she left him cold and bewildered.

"I'm not sure. People are dying by the score in the cities. Starvation and lack of oxygen. It's better here. Williams is right about Canada. But to go there would only delay death that will come sooner or later. If you want to go?"

He looked around with brooding eyes.

"The government is permitting people to pass the border by thousands. I'd rather stay here. It's pleasant here, and familiar."

They all felt that way.

"Answer Jane's question," Lem Waters said. "You can answer it. We ain't afraid."

Gifford looked across the deep lake and at the heavy, green grass and evergreen border.

"Maybe two weeks," he said. "Small, isolated spots like this remain almost intact. Much of the world now it dead. Maybe a month, I don't know."

He shook his head.

They stared down at the dead sapling.

"Hell," Jeff Stern ripped off the apron, "let's go swimming."

After that, Gifford spent his time wandering around the lake, and penetrating the jungle-like growth of the swamp. Five square miles of life, he thought. Five square miles of earth as yet intact.

The fourth day passed.

DORA STERN met him when he came in from the swamp. Dora was almost sixty, a hardened, supple woman who saw much and spoke little. Her eyes were moist as he came into the coolness of the porch.

"Bart," she said, "I want to talk with you."

They walked down to the lake and sat on the wharf.

"Bart," she said, "what are we going to do about Peachy?"

Peachy? What was wrong with her? "I don't think I understand," he said.

"I mean Peachy and the Williams fellow. He's with her all the time. He asked her to run away."

Suddenly he was tense, angry.

"How do you know that?"

She smiled sadly.

"I'm an old woman. I see a lot of things, and maybe I shouldn't snoop around so. They were by the boat house. I heard them talking."

"Is Peachy going?"

"I -- I think so. Williams said we're all crazy. He told Peachy that Canada is safe. I don't think she's safe anywhere with him."

He worried about her all afternoon. They went swimming, Randy Williams, Peachy, Jane and himself. It was sunset and across the lake, he could see the small patches of brown as they seemed to creep down to the water and stop. Small patches of death -- pockmarks on the forest.

Jane stayed close to him. They sat on the raft, watching Peachy and Randy Williams swimming out into the lake beyond the raft.

"Bart," Jane's arm was around his shoulder. "Bart, I'm sorry about last summer."

It startled him.

"I'm not," he said a little stiffly. "It taught me something."

"I was a fool," she said. "I should have married you."

The sun was gone. He could hear Randy and Peachy calling to each other. They were too far out.

"I thought I loved you," he said. "You told me I didn't have a chance. You were mean as hell, Jane, if you know what I mean. You hurt me badly. After a while the hurt went away. I'm not getting into the same mess again."

"Peachy's cry came to him suddenly, a wild, frightened cry.

"Randy -- Randy -- I've -- got -- cramp."

Then a scream, and silence. He was on his feet. A half dozen long steps took him to the deep end of the wharf. Then he went in with a long graceful dive. He came up. He could hear splashing ahead of him and swam swiftly toward the sound. Then her call came again, closer. This time it made his heart cold and sent him ahead with renewed speed.

"Bart -- please."

She had called him.

He was by her side then, and had one arm under her head. He started slowly, dragging her back toward the raft. Then she was on the raft and Randy Williams was bending over her. Peachy opened her eyes slowly.

"Bart -- oh thank God, Bart."

Randy Williams moved away from her slowly, his eyes blazing. Bart went to his knees at her side. "Peachy -- Peachy," he said, and his voice was choked.

Her arms went around his neck. "Bart -- you saved me. Jane -- said -- you ..."

She fainted.

"JANE said you were going to marry her," Peachy said softly. Her arms were about him. Wrapped in the blue beach robe, she clung to him, her eyes wet and happy. "Jane was lying, wasn't she, Bart?"

He nodded, unable to speak. Wondering why he hadn't seen all this before. Peachy -- running away with Williams -- acting strangely toward him.

"I've loved you all along, Bart," she said simply. "I wanted to die. I thought I could go away with Randy -- maybe forget. I couldn't stay, not after what Jane said."

He kissed her, and her lips clung to his.

"Jane lied," he said. He knew she believed it. He had never really loved Jane. It had all been over with since last year. Why had Jane lied? Revenge, because she didn't want him to go to Peachy? He suddenly hated Jane.

"Everything's all right now, Peachy. You're not going to run away?"

Her hair was wonderfully soft and warm against his cheek.

"Not ever," she said, and cuddled close to him. The words were no more than a whisper.

Another week. Nerves were beginning to break. The brown death crawled around the lake. The lawn was dead. The trees, even the hardiest of them, were touched at the top with brown. Brown, dead fingers, creeping down to suck away life.

Jeff Stern met Brad Gifford behind the cabin. He carried a heavy pistol.

"Look, Brad," he said. His face was stony. His eyes were cold as ice. Dora is sick. Her nerves won't take it. Brad, would it be murder to release the person you love from lingering death? Brad, I'm a good man. I don't want to see Dora suffer."

"You can't do that." Brad Gifford wondered if he was right. Who was he to judge mercy killings? Could he make rules? Why the hell did they bother him? He and Peachy were happy. In this last week, he and Peachy were very close. They were crowding a lifetime into a week -- maybe into a month. Why had Jeff come to him?

"You can't do it," he said.

"Why?" Jeff Stern was pleading his case. He had to seek advice. He couldn't do it alone, without someone's approval. Someone had to understand.

"You just can't." Gifford was stubborn.

Jeff Stern put the pistol into his pocket and wandered away. His eyes were dull and unhappy. Dora was lying in the little room at the head of the stairs, her face a pale death mask. She couldn't live long. Her life had been full.

Why did she have to suffer to the end?

Jeff Stern wasn't sure why.

"You can't do it."

"Why?"

JANE STERN avoided Gifford. Her eyes avoided his when they met. She didn't dare speak to him. Gifford had little pity for her now. She had nearly murdered Peachy. Murdered her with unkind words.

Jane went to Randy Williams for comfort. Randy didn't leave the lake. He drove a few miles, and turned back. He shuddered when he thought of that strange, dead world he had started to drive back to. No one on the highway. No living, green things. No people. Most of them had run in panic. Gone to Canada.

It was still green in Canada. For how long?

He went swimming with Jane, but the water was warm and it smelled of dead stuff that floated up from the bottom. Even the underwater plants were dying.

He sat with Jane, trying to derive some comfort from her company. They spoke little. Randy Williams' nerve was about broken, but before he died, he thought, he had one last duty.

If Peachy Waters had gone to Canada with him, he might have escaped.

He might have escaped.

The words kept nagging at him and gradually he placed the blame on Bart Gifford. Gifford had taken Peachy away from him.

He would take something away from Gifford. Take away the person Gifford loved most.

Randy Williams found the pistol on the table in the dining room. Jeff Stern had dropped it there. Listlessly, he had left the weapon in plain sight and wandered upstairs to sit near Dora.

The food was gone. Nothing was left in the garden now, and only a few cans of vegetables were left in the kitchen. A few starved, bony chickens moved listlessly around the chicken yard.

"Maybe a day or two," Gifford said, and he hated to say it for he was pronouncing Peachy's death sentence. Peachy was pale now, but still very beautiful as she sat in the firelight, gazing up at him, worshipping him for his courage and his decency.

They left each other at midnight. Gifford went to bed, but the air was bad. He couldn't sleep. He wondered, what will kill us first? Will it be the poison that rushes in and sucks away our breath? Will it be the heat? Will we starve? Maybe he should have said yes to Jeff Stern. Jeff was right. Dora should be killed peacefully. She shouldn't be forced to suffer.

He gasped for breath, smelling the dry, dead odor of the vegetation outside the open window.

A step sounded in the hall. It came from the direction of Peachy's room. Was she awake, frightened?

He slipped into his robe and went to the door. He entered the hall softly, so that he wouldn't disturb the others.

Randy Williams was standing before Peachy's door. He had a gun in his hand. Before Gifford could speak to him, Williams opened the door and went in quickly. Gifford started to run, hitting the door as it closed. Peachy was sitting up in bed, a blanket pulled about her, eyes wide with horror.

Williams pivoted, smiling grimly.

"Glad you came in, Bart," he said. "Just in time for the party."

His eyes were the eyes of a mad man.

Gifford stood still, legs braced, hoping against hope that Williams would shoot him and spare Peachy. Why, he thought? What difference? We'll all be dead soon.

Still, you didn't die willingly until your time came. You kept fighting, hoping.

"You haven't got the courage to fire that gun," he said. He was lying even to himself. Williams did have the courage, born of desperation.

"It doesn't take courage," Williams said. "Sure, I'm a coward, but I'm damned if you'll talk me out of doing the one thing I can get any pleasure out of."

He had time to pull the trigger, but Peachy was faster. She shot out of bed like a small tigress and was on his back, clawing and dragging him to the floor. The slug tore into the ceiling as Bart Gifford sprang, hitting blindly, pounding Williams down until he lay limp and silent on the carpet. Gifford picked up the gun.

"I guess I better keep this."

Then he went to Peachy.

THEY gathered in Peachy Waters' room. Jenny and Lem Waters were angry. They wanted to kill Williams.

"He isn't worth it," Bart Gifford said. In a way he felt sorry for Williams. Sorry for the man whose courage had failed. Jane Stern sat on the floor, head bowed, holding Williams' head on her lap.

"Where's Jeff?" Lem Waters asked.

Where's Jeff?

Jeff Stern must have heard the shot. "I'm going in and see Dora," Jenny Waters said.

Bart Gifford held her back gently.

"Better stay with Peachy," he said gently. "I -- want to talk with Jeff alone."

In his heart he knew why Jeff hadn't heard the shot.

The old Westerner had taken the law into his own hands. He had made his own law, and he had lived by it.

Dora was dead. A pillow held tightly over her face had snuffed out her life. Jeff Stern was hanging in the bathroom.

He had tied a neat hangman's knot. He had probably tied many of them in his early days, when all men west of the Mississippi made their own laws.

He left a note. It was short.

"Sorry, Bart," Bart Gifford read it with misty eyes. "This time I've made up my mind. There ain't gonna be no more suffering for Dora. Take care of Jane."

Take care of Jane. Gifford tried. He watched her when he could, but Jane shut her door, and behind it nursed Randy Williams. He was better. At least he rested. The wounds didn't heal. The oxygen was bad. The food was worse. Gradually he went mad, and raved about his love for Peachy and his hatred for Bart Gifford. Jane Stern, unloved, needing love, cared for him.

"It's the last day," Gifford said. "Peachy, you and I have to stick together. No fooling each other and no weakening. Your mother died because she wanted to die. Lem wasn't a coward. When your mother died, Lem chose the lake. He loved that lake. He and your mother lived near it all their life. You can't blame Lem for drowning himself, Peachy. It wasn't the act of a coward. It took courage."

Peachy took it well. She watched Bart as he wrapped Jenny's thin body in a blanket and placed her in her grave. There were three graves now. Jenny Waters and Jeff and Dora Stern. The lake had held Lem's body locked beneath its surface. It wouldn't give up its dead.

Upstairs, without food, without hope, Jane Stern watched over Randy Williams.

PEACHY WATERS had grown to womanhood in three weeks. Her childhood was gone. She was thin but the thinness gave her dignity. Her pale cheeks were the cheeks of a woman who faced death with courage, and lived for the love and faith of a man.

She stood on the porch, staring out at the lake, and at the forest beyond.

"Bart," she said, "there's no more green. None at all."

He smiled sadly. He had been careful to shave and to dress neatly. That was a sign of good morale, he told himself. He noticed that Peachy had done the same. Her hair was done carefully, Her dress was colorful and starched neatly. She was like an angel, calm and waiting.

"Maybe. there is a little green somewhere," he said. "It's hard to say. We might find a little. I'd like to see it. I'm starved for a bit of green."

The room upstairs was silent. Jane Stern had never left Randy Williams. She had never come out of the room. No food had gone up for two days. There was no food for Gifford to take to her.

The room was like a tomb, closed and silent, and the door could never open again, for there would be no one left to open it.

"I'd like -- to walk," Peachy said.

She panted a little, for it was hot and there was nothing to absorb the heat of the sun. The earth was scorched and dusty. The lake was very low. Fish floated, stomachs up, on the surface. Crabs lay dry and dehydrated along the shore.

Gifford still wondered at the air he breathed. There was a little oxygen left. Very little that the lungs could use.

He talked only in short sentences. He had to think about breathing or he might forget about it. If he forgot, the poor, shrunken lungs wouldn't work again.

"We'll -- walk," he said.

He took Peachy's fragile hand and they went slowly across the lawn.

He put his hat on Peachy's head to protect her. Her hair, still golden, puffed out under the hat, and he laughed at her.

"You look foolish in that thing," he said.

She laughed a little too, for their minds had ceased to worry about the past. Those dead were forgotten. They might have been the last two people alive on earth. They felt aloof and light headed -- completely alone.

How many more remain, Gifford wondered, as they walked slowly along the lake? How many have managed, as we have, to live for the last day?

The forest was a forgotten place of gray and brown. No wild thing moved among the trees.

They walked for a while without speaking. Then he heard Peachy cry out. It was a surprised, glad cry. She ran into the mass of dried underbrush and fell to her knees. Gifford followed and kneeled at her side.

Suddenly a vague, wild hope gripped him.

"Peachy," he said. "Peachy, maybe -- it's a sign."

She was crying. Crying gladly, as though all her misery was washed away and she was glad again.

Before her, fighting their way out of the brown grass, were two tiny roses. They were sprouting from the seemingly dead stem of a wild rose bush. From the faint green of the stem, two pink roses blossomed. Their color was faded. The rosebush had fought a mighty battle to live.

PEACHY gathered the blooms in her hand without breaking them from the stem. She bent forward and buried her lips in their fragrance.

From the West, a faint, fresh wind started to blow. It carried life-giving oxygen into the valley, rippling the water of the lake, touching the dried limbs of the trees and making them move in the breeze.

The wind was wet. It brought a promise of life.

"Perhaps," Bart Gifford said in a low, reverant voice, "Mother Nature isn't going to die. Perhaps she, with all her power, has felt the healing touch and will revive."

They stayed there for a long time, side by side, watching the two roses with wide, hopeful eyes. Bart Gifford saw the courage and the faith written on Peachy's face.

"She's an angel," he thought. "She's too good to die."

They slept, then, and the two roses felt the touch of dew for the first time in weeks. A few grass blades straightened and started to live. The forest was beginning to feel the touch of a healing hand.